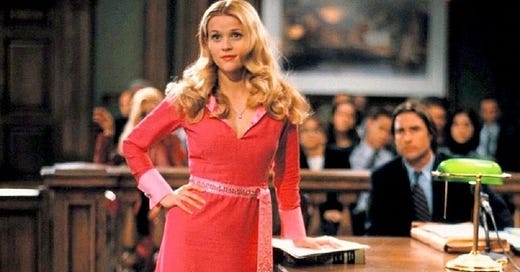

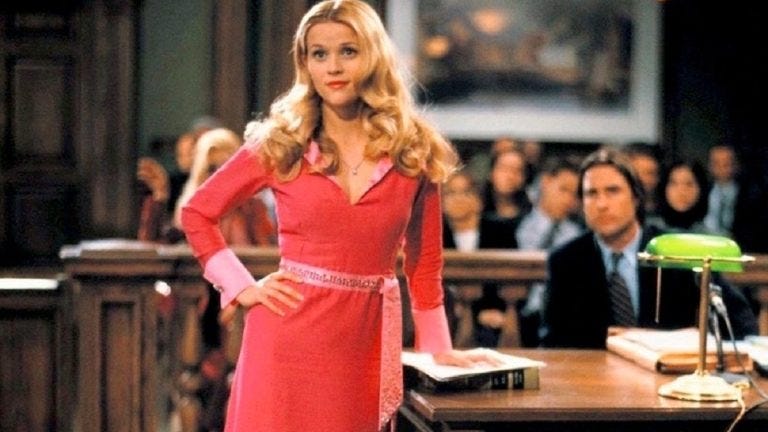

You Better Work Bitch

For Women's History Month, I'm asking one simple question: Can That Girlboss Have It All???

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tangie Dreamz to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.