Not Your Baby, Not Your Mother, Not Your Auntie

I brought you into my world, I can take you right out.

It’s hard to be a woman on the internet. Millennials and up, we’re used to it because we had to be girls on the internet, which is probably harder than being a woman on the internet. We wade through a lot of nonsense, but we stay because there are a lot of good things, too. You can pick up a new hobby, make friends, keep your old friends when you move somewhere new, share memes, music, fashion, whatever.

You join all these little communities, finding your niche. The thing that unifies all of these communities is often influencers. One minute you want to know if the Colourpop Midnight Masquerade palette is worth the trip to Sephora, so you’re typing in the YouTube search bar, and before you know it, you’re knee-deep in someone’s lore. You know all about their ex-boyfriend, their first dog, their old setup in their old apartment, before all the sponsorship deals and affiliate links. It feels like you know them, and it doesn’t even matter if they know you.

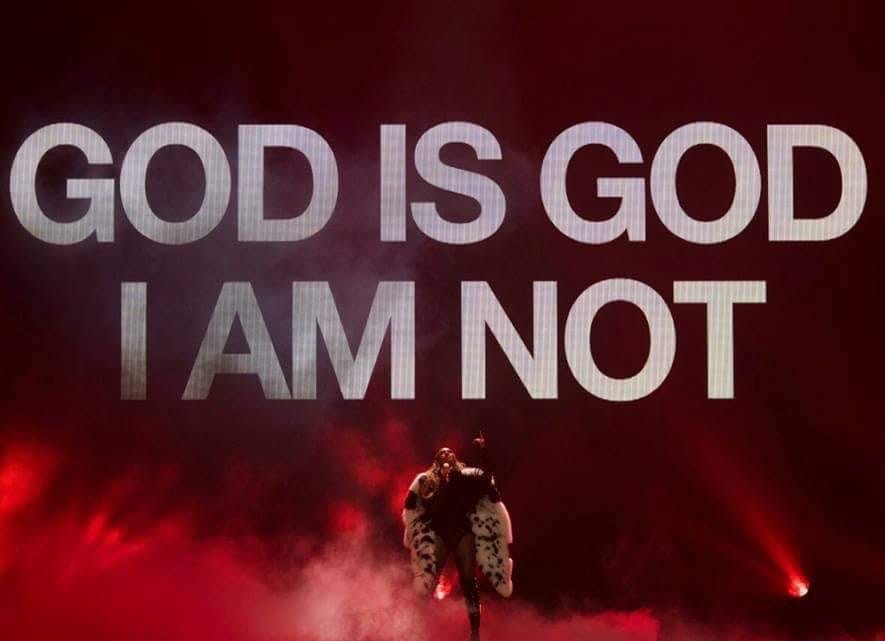

When I think about parasocial relationships (which have existed long before the internet—my first parasocial relationship was with Jesus, thank you very much), I think about the inequity, the inherent power imbalance. Parasocial relationships are often defined by their one-sidedness: I know Beyoncé exists, and I have given her my money, but she doesn’t know I exist. But that’s the thing—in a way, she does know I exist; she knows she has millions of fans across the world. She acknowledges her fans’ existence when she thanks us at the end of her concerts and under posts on her Instagram grid. She also acknowledges our existence when she sets boundaries. She holds her fans at arm's length, never responding to social media comments, rarely giving interviews (is a play-by-play of whatever happened in that elevator ten years ago something you want? Well, let me tell you, you’ll never get it), being highly selective with her public appearances, and reinforcing the idea that we should not worship her.

I also think about that one scene in The Devil Wears Prada, the one where Andy goes to Paris for fashion week. She’s fresh off a breakup and decides to have a one-night stand with a famous, handsome writer whose work she greatly admires. When she wakes up in the morning, late for work and frantically running around handsome writer man’s luxurious Paris pied-à-terre, she comes across the machinations for her boss, Miranda Priestly, to be replaced. When she questions the handsome writer about this, he patronizingly explains that, of course, they are bringing in someone younger to replace her boss—decisions were made, it’s a cutthroat business, but it’s done. Andy incredulously starts rushing out of the apartment to inform Miranda. “Baby, it’s done,” he says to her in the same patronizing tone. But she gets the last word: “I’m not your baby.”

This was made into a gif that was plastered over every moody girl’s Tumblr in the late teens. It was so relatable; there are few things more annoying than a man being patronizing or over-familiar. But being both??? Jail. Immediately jail.

If there’s one person who I’d associate with the comfortability of overfamiliarity right now, it’d be Chappell Roan. Every other day I see a think piece or headline about her asking her fans to respect her boundaries. She created a public persona (Chappell Roan) so she could keep her work and life separate from her private life (Kayleigh Rose). She clocks in at sound check and clocks out after she says “thank you! goodnight!” She doesn’t want you coming up to her in Central Park asking for a picture, she doesn’t want you following her while she’s running errands, she doesn’t want you to tell everyone where her mother and sister live, and she’s not going to endorse a candidate for US president, which seems to be her biggest offense (some of you seriously need to get a grip).

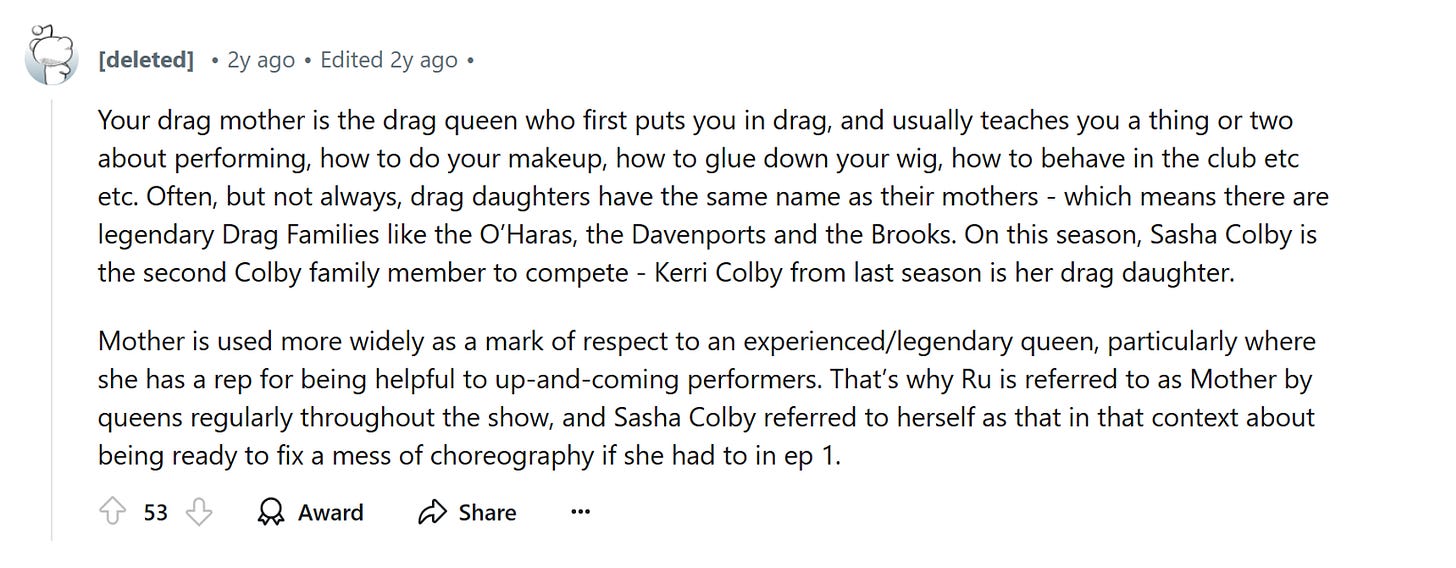

Chappell is (was) “mother,” a term originated in the queer and drag communities to connote someone who guides you through life both in and out of the drag scene. Queer communities often have “chosen families” because their biological families have rejected them out of homophobia. A mother is someone who knows the way and cares for you enough to show you the way. They pass down traditions from their drag houses, providing shelter, food, love—things supposed to be provided by a biological mother who has (often out of choice and bigotry) decided to forego that. As a Reddit commenter explained, a mother is:

I know we live in a time where words barely mean anything anymore, but it feels unfair to put all of that on a 26-year-old who’s just getting started in their career, no matter how good “My Kink Is Karma” is.

I started thinking about all of these things because I was thinking about Jackie Aina, a popular beauty influencer who got her start on YouTube and now posts predominantly on TikTok. In 2022 TikTok, Aina kindly asked her followers, fans, and viewers not to call her ‘auntie.’ To be honest, I wasn’t sure how to feel about her request when I watched the video. Of course, I was going to respect her wishes, and I don’t tend to comment or interact with influencer content outside of watching it anyway, so that wasn’t hard. It was more that I was really analyzing what she was asking.

This is true for many cultures worldwide, but I can really only speak for my own Black experience: “auntie” is a title that holds weighty implications. Assigning familial labels and roles to non-biological family is something that started during the transatlantic slave trade. It was a survival tactic; on slave ships and plantations, adults taught the children to refer to elders as “auntie” and “uncle” for two reasons: it socialized children into the enslaved community and created a bond and context for a reciprocal relationship.1 Children were separated from their families both before and after being dragged across the world. Adults recognized the need for structure and kinship, so they created it. That’s what is called fictive kinship; chosen family, creating bonds that aren’t reinforced by blood or marriage, but a secret third thing (usually white supremacist capitalist patriarchy).

This practice of fictive kinship never went away; if you’re Black, you probably have an “auntie” (“ainnie”) and “unc” that isn’t your mother or father’s sibling. When one of my oldest friends told me she was pregnant, she started the message by telling me “You’re gonna be an auntie!!!”2 She has a wonderful family and a great support system, so outside of our shared practice of fictive kinship, there was no reason for her to refer to me as an auntie in relation to her new (beautiful) baby. But by letting me know I was going to be an auntie, she is acknowledging and reinforcing both our friendship and our shared Blackness. I took that message to heart and took up my role by knitting my new nephew a baby blanket that now hangs in his crib. Both she and I are interacting under this premise because we, like our ancestors (to a far lesser extent), are using the traditional practice of fictive kinship to adapt to the changes in our lives.

Kinship obligations were extended beyond customary adult-child relationships to encompass both unrelated adults and unrelated children within slave communities. These fictive kin relationships functioned to integrate adults in informal supportive networks that surpassed formal kin obligations conventionally prescribed by blood or marriage. Actual or genuine kinship bonds served as the models for affective obligations among non-kin; these responsibilities were then transferred into broader social and communal obligations.3

These relationships are informal and “can be relinquished at any time.” Essentially, yes, it is that deep but it’s not that serious.

So, when Aina asks people not to call her auntie, it’s likely because she’s taking all of that into account. As she explained in her video, she never felt like she had genuine time to be young. From what I know about Aina, she’s the eldest of six, had a difficult childhood, at some point living in domestic violence shelters, she’s an Army reserve veteran, and was married and divorced at a young age. Aina is 37 years old, which is still young. She started her YouTube channel at 22 as a way to cope with her life at the time and as a way to show girls with darker complexions how to do their makeup.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Aina explains that people older than her call her “auntie” and it’s jarring to her; she wants to look up to others instead of others looking up to her all the time. She laments always having to act older than she is as a survival mechanism and says she’s finally “reclaiming her time.” She makes it clear that she doesn’t want younger people calling her auntie either.

It actually makes me a little bit sad because these are people that are at the age when people started calling me ‘auntie.’ How come when I was that age I still had to be—why couldn’t I be young when I was actually young?"

I saw the response to this in real-time, and it was a shitshow. People came out of the woodwork with speculations, rebuttals, and conspiracy theories. Jackie Aina wasn’t just setting boundaries informed by her experiences and communicating how she wanted to move forward—no, no. She was insecure about aging, she’s too uppity for us commonfolk, this is nothing new, she’s always been rude. Then there were people asking if they could still call her “sis” because if not, that would be a huge blow for their parasocial relationship. Earlier this year, TikTok and Twitter users speculated that Aina was mass-blocking people for asking if she had gotten married—she was not.

Aina was clearly and calmly setting a boundary with viewers in an attempt to reclaim a component of her autonomy. To do that, she needed to break out of a generational cycle, one that asks Black girls to grow up too fast, to take full responsibility for their communities, even their parasocial ones, which have the potential to be more intense than a parasocial relationship with a traditional celebrity.4 In a time where the concept of generational trauma is at the forefront of discourse and eldest daughter TikToks and essays are rampant, Aina understands the effect her childhood had on her development into adulthood. In the age of self-care and mental health, Aina communicated that she didn’t have the capacity to fulfill the role of auntie, and in an (un)surprising turn of events, the community threw it back in her face.

I think this is because women are expected to comport themselves for the comfort of those around them. Women are supposed to consistently perform upkeep, not only of themselves but of their communities. Ask any given father when his children’s birthdays are or who their friends at daycare are. Does your boyfriend know his grandmother’s birthday? Is your brother inviting everyone over to his place for Christmas? The answer may be yes for a small number of people, but for most, the answer is no. Who's doing the dishes after dinner? Who’s decorating the apartment? Who’s feeding and clothing the kids? This is women’s work, and many women are socialized into these scripts by a combination of things—including watching their parents’ dynamics, social pressure, and a common and well-publicized fear of ending up as a childless cat lady, supposedly unhappy, unwanted, and alone.

The people (usually women) in families who do that work are called kinkeepers. They’re your mothers, grandmothers, and yes, aunties.

References to kinkeepers began cropping up in sociology literature in the mid-20th century. Researchers defined the role as a family communicator who helped the extended group stay in touch by sharing family news and planning gatherings.

In recent decades, sociology and psychology researchers have expanded the definition to include things like creating or carrying on family traditions, buying gifts for birthdays and holidays, coordinating medical care, and performing all sorts of emotional caregiving.5

For women of color, there is an even deeper layer. The fictive kinship passed down to us from our ancestors may mean that intra-communally, we are held to extraneous standards of kinkeeping for those around us. We’re taught that we are part of a community (Black, Latine, Asian, etc.) and we need to look out for those in that community in a way that white people do not. (This is why it’s jarring when a non-Black person calls me ‘sis,’ or when I see non-Black people using ‘unc’ on the internet… “they not like us” means you too!) When someone disregards that, it can look like an alignment with or a desire for proximity to whiteness when in fact, they are trying to break a toxic generational cycle.

Like I said at the top, it’s pretty hard to be a woman on the internet. If TikTok or Twitter are any indication, existing as a Black woman on the internet has proven to be a hazardous task. Black men kowtow to white men, chuckling about how undesirable you are. Did you make a sensible critique about a faulty product? Prepare to be cyberbullied off the internet. Men on the left may also be using you as currency, trying to up their woke points with saccharine sentiments about how much they love Black women6—even though they don’t currently seem to be in community with any.

These are all things I have to take into consideration as a (Black) woman on the internet and in real life. What do I want to be regarded as, as I age? In some ways, my parents shielded and sheltered me from a lot of things, so I wouldn’t feel the pressure of needing to grow up too fast. On the other, I was definitely socialized to do traditional women’s work, and to do it diligently. I have two sewing machines, I cook, I clean, I moved to a foreign country and have hosted a few successful Thanksgiving dinners, insisting that I cook and decorate everything myself. There’s a delicate mix here, of me doing all of that on my own terms and doing it because I was programmed that way. But as I enter the era where my friends start having babies and people ask me if I want my own babies, I, like Aina, have to make a choice for myself.

Personally, the idea of my best friend’s baby calling me auntie fills me with an unimaginable joy that I can’t wait to experience in real life. I think the idea of some youngin’ on the internet calling me, an eventual old head, auntie would be cool, too; it would be a reflection of the hard work I put in to build an online community. But don’t get over-familiar, baby; like the old Black proverb (kinda) goes: I brought you into my world, I can take you right out.

Mills, Ciyrtal S., et al. “Kinship In the African American Community.” Michigan Sociological Review, vol. 13, 1999, pp. 28–45. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40969034.

Coincidentally, we have the same last name, but we aren’t related by blood or marriage.

Chatters, Linda M., Robert Joseph Taylor, and Rukmalie Jayakody. "Fictive Kinship Relations in Black Extended Families." Journal of Comparative Family Studies, vol. 25, no. 3, Autumn 1994, pp. 297-312. University of Toronto Press, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41602341.

Lin, Carolyn A., Julia Crowe, Louvins Pierre, and Yukyung Lee. "Effects of Parasocial Interaction with an Instafamous Influencer on Brand Attitudes and Purchase Intentions." The Journal of Social Media in Society, vol. 10, no. 1, Spring 2021, pp. 55-78, thejsms.org.

Friedman, Danielle. "The Constant Work to Keep a Family Connected Has a Name." The New York Times, 8 May 2024.

I don’t usually like to encourage spending time on Twitter but the linked video and comments under it were…interesting to say the least!